Why do literary writers so often languish in the dark? And why do I, a Christian writer, find myself tending there, too?

I think of Sylvia Plath who longed to succeed at writing so badly that it drove her entire life, and who eventually found success–only to kill herself. Her journal is full of amazing writing, by the way—lilting, lyrical writing that wowed me—but by the end, when I had to face the reality of a journal, and a life, prematurely cut short, I had to conclude: It wasn’t worth it.

That said, let me make a confession: I started out in the dark, too. (Oh, that word darkness is so fraught with metaphor, but let me hold off for a moment.)

I merely mean I wrote dark things—when I really started writing (age 14)—because my life had gone dark. There were certain things happening at home that I couldn’t talk about. Dark things. Embarrassing things.

I wrote in the dark, too (again, resisting the full metaphorical connotations). I mean, I wrote at night. Not only did my student schedule make nighttime the best time, but it just seemed fitting. Until after I got married, I remained a night writer, letting the day’s darkness inspire that in me to come out.

From my background in literature, it seems to me that a lot of great writers drew their inspiration from suffering. Some tragedy from childhood—or some shocking turn in adulthood. Why would a person, and how could they, write of darkness without living it? Why would they want to?

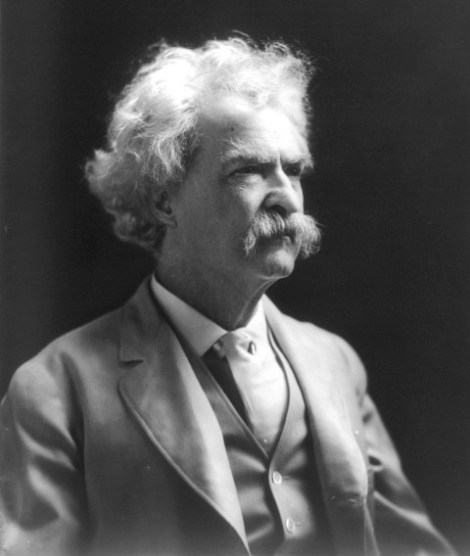

Mark Twain, commonly dubbed a humor writer, actually turned darkly pessimistic in his later years after losing his daughter.

Mark Twain, commonly dubbed a humor writer, actually turned darkly pessimistic in his later years after losing his daughter.

You remember that highly anthologized story “The Yellow Wallpaper” with the unreliable (read: crazy) narrator? The author, Charlotte Perkins Gilman ended up killing herself, as did the popular Virginia Woolf.

Alcoholism ran in William Faulkner’s family, and Eugene O’Neil’s mother was addicted to morphine (this is depicted in his play Long Day’s Journey into Night).

T.S. Eliot had a nervous breakdown, and Ezra Pound died in an insane asylum.

From my American Literature class, I can remember a slew of writers whose fathers died in their youth or abandoned them, including Mark Twain, Stephen Crane, and Tennessee Williams.

And Sylvia. Poor Sylvia lost her father before the tender age of ten. She obviously never recovered, but for a period of years she was able to cover her pain with a slew of academic and literary achievements.

I see a lot of myself in Sylvia. Correction. A lot of my old self.

Poor Sylvia never found light. I did. I recovered a will to live as well as developed a prayer life. I decided my still forthcoming memoirs would not be all doom and gloom and “poor me, pity me,” but rather, “Look what God can bring forth from doom and gloom” and “Learn from me.”

And yet…

And yet…

I just had a conversation with a good friend in which I confessed: “I still find myself wanting to write mainly melancholy—I have to work to write positively. I worry that this blog gets too dark sometimes.”

She reassured me that, although, yes, I get a bit dark sometimes, there’s always hope inherent. “It’s a good mix,” she says. “And maybe it will help someone going through similar things.”

Can I make a spiritual/biblical application here?

My Characteristic Glimmer of Hope

In the past year, I’ve started marking metaphors I find in my Bible. I have a dream of teaching a college literature class that explores the figurative language in the Bible—it is so rich!

One of the recurring metaphors I find is that of light and dark.

This is so meaningful to me because of the darkness I’ve felt in my life—and more so just in me. The Bible tells me that Jesus came to shed light on my darkness. He is the Light of life. But the world did not recognize Him because they loved darkness (See Luke 1:78-79; John 1:3-5, 10; 8:12; 1 John 1:5).

I love the image of my Lord and Savior shining light on me—illuminating my narrow and closed mind, drawing me out of the night’s blackness into the morning light, warming my frigid insides.

Oh, He knows me so well! He knew what I would need—His light! Oh, Lord, more of your light!

But these remaining shadows! What of these mixed blog posts of light and dark? It’s like a struggle is going on in my soul.

The sobering reality is: There is a struggle going on in my soul. The enemy is clearly still fighting for me—he wants me back, that jerk. But I have no intention of going back.

And yet…those shadows.

Sometimes I wonder if going back on depression meds could help brighten my discouragingly-default-like pessimism. And then I remember that over six years, they never helped me as much as inviting Jesus into my heart. And I go back to my Bible to read that no pill could change the real problem (my fallen human nature), not unless it were God-sent manna-Prozac.

So—here’s my real gem of hope for today—maybe my mixed blog posts are churning out of my insides in the way they do to serve as a reminder, to me, to you, that there is a battle going on every day in our souls—and it won’t be over until God comes.

“Therefore, we do not lose heart. Though outwardly we are wasting away, yet inwardly we are being renewed day by day. For our light and momentary troubles are achieving for us an eternal glory that far outweighs them all. So we fix our eyes not on what is seen, but on what is unseen, since what is seen is temporary, but what is unseen is eternal” (2 Cor. 4:16-18).